The election is finally over … mostly. With the dense fog of Election Day politics beginning to clear, policy insiders’ attentions return to the issues that had dominated their daily discussions in the weeks and months prior to November 3.

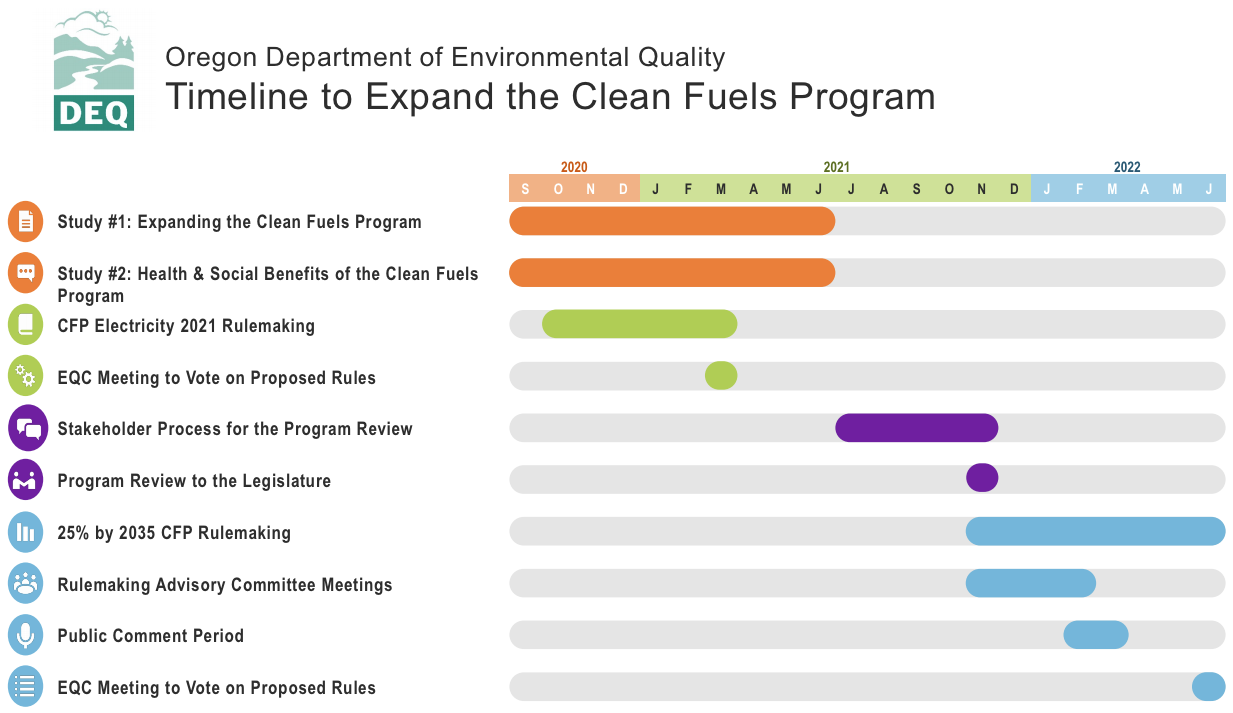

Oregon, which has both a Renewable Fuel Standard and Clean Fuels Program in effect, might provide an example of how such programs could co-exist at the national level. [Click here for full image]

For the energy and agriculture industries, one of the biggest policy issues leading up to the presidential election was executive branch support for the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) … or lack thereof. In August 2020, the Biden campaign took aim at the Trump administration’s handling of the program.

“Instead of standing with those who till our land and sow our fields, we have a president who has sold out our farmers by undercutting the Renewable Fuel Standard with the granting of waivers to Big Oil,” Biden said. “Those waivers severely cut ethanol production, costing farmers income and ethanol workers their jobs. Now, President Trump refuses to announce the 2021 renewable fuel production levels until after the election, leaving farmers concerned of further cuts to production. The Renewable Fuel Standard marks our bond with our farmers and our commitment to a thriving rural economy.”

Now that Trump is on his way out and Biden in, conversations around the RFS have shifted. It’s no longer so much a question of will the next presidential administration support the use of renewable fuels, but rather how will it do so. The RFS sets minimum biofuel production levels up until 2022. After that point, the program continues to exist, but production volumes are established by the EPA in coordination with the Secretary of Energy and Secretary of Agriculture.

Will the RFS be replaced by a national version of California’s Low-Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS), as Democrats have recommended in policy documents circulated this year? Or will the U.S. have both the RFS and a nationwide LCFS in effect? As our title asks, is it a both/and or either/or situation?

The both/and scenario might sound redundant to some, but there are significant differences between the standards. One state in the Northwest offers a working example of these differences, as well as a precedent for how the two programs might function in tandem with each other.

Mandates & Incentives

Oregon adopted an RFS in 2007 for ethanol, biodiesel and renewable diesel. The program mandated that all gasoline sold in the state must be a minimum E10 (10 percent ethanol) and that all diesel sold in the state must be a minimum B2 (2 percent biodiesel) by 2009. After Oregon’s biodiesel production capacity reached 15 million gallons in 2010, the diesel standard increased to B5 in 2011.

This standard essentially established a floor, or mandated minimum level, for the renewable component of the state’s transportation fuels. Unlike the national Renewable Fuel Standard, the state program did not establish a marketplace for Renewable Identification Number (RIN) credits. Instead, the state offered various tax exemptions and loans to help incentivize renewable fuel adoption.

This changed in 2016 when Oregon implemented its Clean Fuels Program (CFP), a low-carbon fuel standard modeled after California’s LCFS program. Rather than set minimum blend levels, the CFP establishes annual average carbon intensity standards with which regulated parties (e.g., gasoline or diesel importers, and ethanol or biodiesel producers) must comply.

The CFP required a .25 percent reduction in carbon intensity in 2015, scaling up each year to a 2.5 percent reduction in 2020 and a 10 percent reduction in 2025. Deficits are generated when the carbon intensity of a specific fuel exceeds the CFP standard, and credits are generated when the carbon intensity of a specific fuel is lower than the CFP standard. Regulated parties that generate deficits must purchase credits, typically from renewable fuel producers.

In the most basic terms, an LCFS is to incentives what an RFS is to mandates.

Note that although the LCFS provided added incentives to transition Oregon’s transportation sector from fossil fuels to renewable energy, the state’s RFS mandates remain in effect, requiring a minimum E10 gasoline and B5 biodiesel even while distributors and retailers successfully sell higher blends at the pumps.

Floors, Yes – Ceilings, No

Might a dual RFS/LCFS model function at the federal level in a way similar to Oregon’s RFS/CFP standards? If so, questions would need to be answered about the point of obligation and regulated parties, as well RIN credits and the ever-controversial small refinery exemption (SRE) process.

One imagines the sheer amount of paperwork that would be involved in establishing dual clean-energy standards would likely be enough to delay program implementation until 2022. That being said, the prospect of a program with a concrete “floor” of renewable fuel mandates and no “ceiling” on blending incentives might find champions among environmental advocates as well as oil companies that are now voluntarily transitioning to biofuel production.

For now, the general direction of future climate and energy policy rests, along with the fate of any specific legislation, in the hands of the incoming Congress, whose control will be determined in January by Georgia’s two run-off elections.

As a final consideration, it should be noted that national LCFS programs have been proposed before, in 2009 and 2007. Readers might recall that one proposal, the National Low Carbon Fuel Standard Act of 2007, was put forward by a senator from the state of Illinois by the name of Barack Obama.